---

title: "Historical low temperatures in Fort Collins, Colorado"

date: 2023-02-10

author:

- name: Daniel Burcham

orcid: 0000-0002-1793-3945

description: "Use the `extRemes` R package to fit extreme value distributions to daily low temperatures"

image: Effective-100-year-return-levels.png

categories:

- r

- tidyverse

- ggplot

- extreme values

---

```{r}

#| code-fold: true

library(knitr)

knitr::opts_chunk$set(fig.width = 7, fig.align = "center",

fig.retina = 1, out.width = "90%",

collapse = TRUE)

```

## The dead of winter

Recently, the Colorado State University weather station recorded a daily

low temperature of -15.4° F in the early morning of 22 December 2022. At

the time, wind chills varying between -50° and -35° F threatened lives

across most of the Eastern plains in Colorado. The frigid temperatures

accompanied a string of unpleasant winter weather for much of the US

with many places experiencing bitter cold, gusty winds, and heavy snow;

and the unfortunate timing of the weather only compounded the

frustrations of many people traveling over the holidays.

Cold weather snaps are common in Colorado, and the plants and people

living here must equally tolerate occasional severe freezing.

Fortunately, many trees easily endure freezing temperatures during the

winter months - the vegetative buds on most deciduous broadleaf trees

withstand temperatures between -13°F and -37° F (-25° and -35° C).

Occasionally, though, some cultivated trees are injured or killed by low

temperatures, especially if temperatures drop abruptly after relatively

warm weather (e.g., *false springs*) or the species was introduced from

a milder climate. The sudden freezes can be especially harmful if trees

are not acclimated to cold temperatures; the events can damage buds,

leaves, and flowers and, in some cases, disrupt water conduction or

natural growth patterns. In recent years, for example, several freeze

events killed large numbers of Siberian elms (*Ulmus pumila*) along the

Front Range, and I have heard similar stories about widespread tree

damage caused by unusual fall freezes in earlier decades.

## Freezing tolerance in trees

Trees use a number of strategies to tolerate freezing temperatures

during winter, including withdrawing water into non-living tissues where

ice formation avoids damage to living cells, lowering the freezing point

of the water retained in cells, and forming physical barriers

restricting the propagation of ice crystals. As temperatures fall below

freezing, extracellcular ice draws out some of the water retained in

living cells along an osmotic gradient between the two phases of water,

and trees further modify their living cells to tolerate the dehydration

during freezing. In addition to leaf shedding, the modifications are all

part of a tree's yearly preparations for the winter season.

Unfortunately, smooth transitions are not part of Colorado's weather

patterns. Highly variable and adverse weather conditions prevail over

the region's semi-arid landscapes, and trees unaccustomed to such

variability may be at greater risk of freeze damage.

The seasonal pattern of cold hardiness is U-shaped with trees

increasingly hardy to lower freezing temperatures during fall,

consistently hardy to minimum temperatures during the winter, and

decreasingly hardy during the spring. Crucially, the timing of seasonal

transitions ensures that a tree's physiological activity matches

changing environmental conditions. There is broad agreement that day

length and temperature mainly govern the acquisition and loss of cold

hardiness, respectively, in the fall and spring each year, but

individual tree species also display a unique sensitivity to the two

seasonal environmental cues for spring emergence. Some species, like

green ash (*Fraxinus pennsylvanica*) and Siberian elm, are more

sensitive to temperature during bud burst in the spring, and others,

like white ash (*Fraxinus americana*) and littleleaf linden (*Tilia

cordata*), are more sensitive to day length during the same transition.

The heavy reliance on fickle temperatures for seasonal transitions may

explain the winter damage more commonly observed on the former two

species, but the seasonal cues for many species are also moderated by a

chilling (accumulated low temperature) requirement that, if unfulfilled,

prevents premature bud burst.

For a given species, the precise timing of spring budburst is determined

by the maximum cold hardiness, low winter temperatures (chilling), warm

spring temperatures (forcing), and increasing spring day length

(photoperiod). In many places, scientists have observed a steady

advancement of biological spring towards earlier times of the year amid

the warming climate, and the risk of freeze damage during false springs

may be especially significant for trees, depending on the rate of cold

hardiness loss during spring. In Colorado, wild temperature fluctuations

are already commonplace in the spring and fall, and many people have

learned to simply avoid trees tending to leaf out early or retain leaves

late in a season.

## Statistics of extremes

Recently, I received a summary of extreme low temperatures in Fort

Collins in the 20^th^ Century, and the report clearly showed that our

predecessors on the Front Range endured *much* colder days. In fact, it

is difficult to imagine the landscape and conditions encountered by

early settlers before all the roads, houses, and McDonald's. The small

patches of preserved steppe offer mere glimpses of pre-settlement

landscapes, but the near complete absence of trees from the native

shortgrass prairie reflects the region's poor suitability for large

woody plants. Without deliberate care from people, our community forests

would not thrive. Curious about historical temperature trends, I decide

to update the summary with more recent observations and explore the use

of extreme value analysis to characterize severe freezing events in Fort

Collins using the `extRemes` package in `R`. Instead of evaluating more

commonplace conditions, extreme value distributions depict the

occurrence of maximum (or minimum) values in a data set. Usefully, they

can statistically characterize extreme climate processes without a

mechanistic treatment of the underlying physical phenomena. They have

been used to describe the probability of very rare or extreme events,

such as severe "100-year" floods, and they have yielded important design

criteria for engineers anticipating the limits of environmental

conditions affecting buildings or infrastructure. For many, the models

can also be confusing when the frequency or magnitude of real world

events differs significantly from predictions based on historical data.

{.lightbox #fig-marker width=50%}

For example, I often ride past a marker in

Creekside Park (@fig-marker) showing the magnitude of a severe flood on July 28, 1997

in Fort Collins. After a torrent of rain fell in a short period of time,

Spring Creek overflowed and washed out large areas of the community. Ultimately, the storm caused millions in property

damage, dozens of injuries, and five fatalities, and the experience led to many improvements in stormwater management and flood preparedness. The marker depicts the

unprecedented magnitude of the flood by comparing it to the much smaller

5-, 10-, and 100-year flood levels.

Despite its longstanding use in the physical sciences, the techniques

can also be used to understand biological phenomena. I first encountered

extreme value analysis in a

[study](https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1990.35.1.0001) examining the

stochastic forces of crashing waves on limpets in rocky shores, and the

authors sought to quantify the probability of an extreme wave-induced

force potentially dislodging the aquatic snails. The cumulative density

function (CDF) for the Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution can

be defined as:

$$F(x;\mu,\sigma,\gamma)=e^{-[1-\gamma(x-\mu)/\sigma]^{1/\gamma}}$$ {#eq-GEVD-CDF}

where $\gamma\ne0$ and $[1-\gamma(x-\mu)/\sigma]>0$. The three

parameters $\mu$, $\sigma$, and $\gamma$ depict the location, scale, and

shape of the distribution. The location parameter, $\mu$, represents the

most common, i.e., modal, extreme value. The scale parameter, $\sigma$,

portrays the rate of change in $x$ with the natural logarithm of time,

and the ration $\sigma/\gamma$ represents the maximum extreme value. The

return level, $x$, associated with a return period, $T$, corresponds to

the $1-p$ quantile of the distribution, where $p=1/T$. For example, a

100-year return level would correspond to the $1-{1\over100}=0.99$

quantile. Return levels can be obtained using the quantile function:

$$F^{-1}(1-p;\mu,\sigma,\gamma)=\mu+(\sigma/\gamma)\{{1\over[-ln(1-p)]^\gamma}-1\}$$ {#eq-quantile-function}

where $\gamma\ne0$. The interpretation of a return level often causes

confusion, but it is simply the value expected to be exceeded, on

average, once every $T$ years.

The `extRemes` package was developed by Eric Gilleland, a CSU graduate

now working at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder,

and it has facilitated greater interest and use of extreme value

statistics by many more people, including me! To update the data, I

consolidated the 20^th^ Century weather data from Fort Collins contained

in `extRemes` with more recent observations from the same weather

station. Today, the weather station is situated on the main campus of

CSU near the Lory Student Center, but the station was initially operated

near the former "Old Main" building with observations starting on 1

January 1889. Maintained by the Department of Atmospheric Science, the

station offers one of the oldest weather records in the state.

```{r libraries-data-graphics, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE}

#| code-fold: true

library(tidyverse)

library(ggtext)

library(extRemes)

library(gridExtra)

library(kableExtra)

library(httr)

library(jsonlite)

library(modelsummary)

library(showtext)

# Load FCwx data from extRemes package

data(FCwx)

# Query updated FCwx observations and combine

api <- GET("https://coagmet.colostate.edu/data/daily/fcl01.json?from=2000-01-01&to=2022-12-31&fields=tMax,tMin,precip")

FCwx2k <- do.call(cbind.data.frame,fromJSON(rawToChar(api$content))) |>

mutate(dt = as.Date(time,"%Y-%m-%d"), Dy = yday(dt), Mn = month(dt), Year = year(dt)) |>

select(dt,Dy,Mn,Year,tMin) |> rename(MnT = tMin)

FCwx <- FCwx |> mutate(dt = as.Date(paste(Dy,"-",Mn,"-",Year),"%d - %m - %Y")) |>

select(dt,Dy,Mn,Year,MnT)

FCwx <- bind_rows(FCwx,FCwx2k) |> mutate(doy = yday(dt))

FCwx <- FCwx[FCwx$MnT != -999,]

#windowsFonts(Inter = windowsFont("Inter"))

font_add_google("Inter","inter")

showtext_auto()

theme_nice <- function() {

theme_minimal(base_family = "inter") +

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.spacing.x = unit(25, "points"),

plot.title = element_text(family= "inter", face = "bold"),

axis.title = element_text(family = "inter"),

strip.text = element_text(family = "inter", face = "bold",

size = rel(1), hjust = 0),

strip.background = element_rect(fill = "grey80", color = NA))

}

update_geom_defaults("label", list(family="inter"))

update_geom_defaults(ggtext::GeomRichText, list(family="inter"))

```

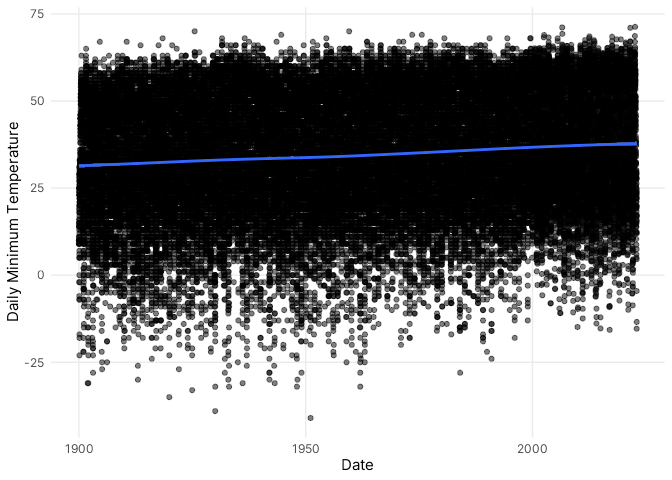

Upon inspection, the data revealed some obvious patterns. Between

`r min(format(FCwx$dt,"%Y"))` and `r max(format(FCwx$dt,"%Y"))`, there

were `r format(sum(FCwx$MnT < 32, na.rm = TRUE),big.mark=",")` days with

low temperatures below freezing in Fort Collins (approximately 44% of

all observed days). Recorded on

`r format(FCwx[FCwx$MnT == min(FCwx$MnT),1], "%d %B %Y")`, the coldest

daily low was `r min(FCwx$MnT)`° F! Wow, that's really cold. Near the

lower limit of the observed range, there were

`r sum(FCwx$MnT < -20, na.rm = TRUE)` days with low temperatures below

-20° F, but such extremely cold days were not observed uniformly over

the past 122 years:

`r round((nrow(FCwx |> filter(MnT < -20 & format(dt,"%Y") < 1950)) / sum(FCwx$MnT < -20, na.rm = TRUE)),3)*100`%

of the events occurred before 1950.

```{r global-plot, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE, fig.showtext= TRUE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: fig-global-plot

#| fig-cap: "Daily minimum temperatures in Fort Collins, CO between 1900 and 2022"

ggplot(data=FCwx,aes(x=dt,y=MnT)) +

geom_point(alpha=0.5,position="jitter") +

geom_smooth() +

xlab("Date") + ylab("Daily Minimum Temperature") +

theme_nice()

```

In the entire data record (@fig-global-plot), there is an obvious upward

trend in daily minimum temperatures over time, and you can also clearly

see more variability around the lower limit of observations. As a

convenient starting point, I simply fit a GEV distribution to all

observations. The location parameter for the preliminary fit, for

example, indicated that the most common daily minimum temperature was

41.6° F (@tbl-fit0). For such cases, one important modeling assumption

requires the use of homogeneous data obtained from a process *not*

undergoing any systematic change. In many cases, however, extreme value

processes exhibit slowly-varying or cyclical behavior, and the

probability of an extreme event, often, varies according to diurnal,

seasonal, or annual conditions. Apart from significant seasonal

variation, the long-term trend towards warmer daily low temperatures in

Fort Collins likely violates this assumption.

```{r initial-fit, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: tbl-fit0

#| tbl-cap: "Parameter estimates for stationary Generalized Extreme Value distribution fit to negative daily minimum temperatures in Fort Collins, CO between 1900 and 2022"

# Fit stationary model

fit0 <- fevd(-MnT ~ 1, FCwx, type = "GEV", span = 123, units = "deg F", time.units = "days", period.basis = "year")

# Stationary model summary table

fit0.summary <- summary(fit0, silent=TRUE)

params.ci.fit0 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit0, type = "parameter"),ncol=3))

colnames(params.ci.fit0) <- c("ll","est","ul")

fit0.model.summary <- params.ci.fit0 |>

mutate(estimate = paste(round(params.ci.fit0$est,digits=2)," (",round(params.ci.fit0$ll,digits=2),", ",round(params.ci.fit0$ul,digits=2),")", sep = "")) |>

select(estimate)

fit0.model.summary <- data.frame(params = c("Location, μ","Scale, σ","Shape, γ"), fit0.model.summary)

footnote(kbl(fit0.model.summary, format="html", booktabs=TRUE, col.names=c("Parameters", "Estimate (95% CI)"), row.names=FALSE, digits=2, align="lc", escape=FALSE) |>

column_spec(1,width="10em") |>

column_spec(2,width="12em") |>

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position="left"), paste("Negative log-likelihood (NLLH): ",round(fit0$results$value,2),"; Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): ",round(fit0.summary$BIC,2), sep=""), footnote_as_chunk = TRUE)

```

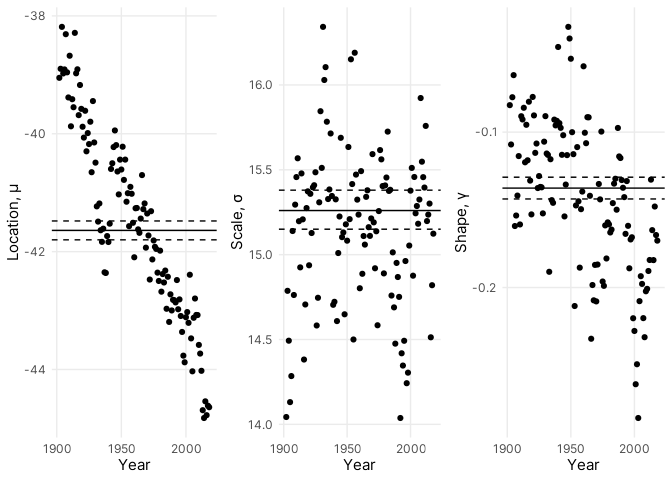

Fortunately, it is possible to account for non-stationary extremes by

directly modeling variation in the distribution parameters. To explore

variation in the distribution parameters over time, I fit multiple

stationary GEV distributions to short, overlapping five-year segments of

the data between 1902 and 2018.

```{r moving-fit, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE, fig.showtext=TRUE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: fig-moving-fit

#| fig-cap: "Generalized Extreme Value distribution parameters fit to running five-year windows of daily minimum temperature in Fort Collins, CO between 1902 and 2018"

# Fit GEVD using running five-year windows between 1902 and 2018 and store result

mnt.yrs <- list()

for (i in 1902:2018){

mnt.yrs[[i-1901]] <- fevd(-MnT ~ 1, FCwx |> filter(format(dt,"%Y") == seq(i-2,i+2)), type = "GEV", span = 5, units = "deg F", time.units = "days", period.basis = "year")

}

locs.yrs <- data.frame(years = seq(1902,2018),locations = matrix(unlist(lapply(mnt.yrs,'[[',c(20,1,1)))))

scls.yrs <- data.frame(years = seq(1902,2018),scales = matrix(unlist(lapply(mnt.yrs,'[[',c(20,1,2)))))

shps.yrs <- data.frame(years = seq(1902,2018),shapes = matrix(unlist(lapply(mnt.yrs,'[[',c(20,1,3)))))

p1 <- ggplot(data=locs.yrs, aes(x=years, y=locations)) +

labs(x = "Year", y = "Location, \u03bc", escape = FALSE) +

geom_hline(yintercept = -41.64) +

geom_hline(yintercept = -41.8, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_hline(yintercept = -41.48, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_point() + theme_nice() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1900, 1950, 2000))

p2 <- ggplot(data=scls.yrs, aes(x=years, y=scales)) +

labs(x = "Year", y = "Scale, \u03c3") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 15.26) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 15.15, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 15.38, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_point() + theme_nice() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1900, 1950, 2000))

p3 <- ggplot(data=shps.yrs, aes(x=years, y=shapes)) +

labs(x = "Year", y = "Shape, \u03b3") +

geom_hline(yintercept = -0.136) +

geom_hline(yintercept = -0.143, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_hline(yintercept = -0.129, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_point() + theme_nice() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1900, 1950, 2000))

grid.arrange(p1,p2,p3,nrow=1)

```

The estimates show obvious variation in the location parameter over the

examined years with the modal (negative) daily low slowly decreasing

(increasing) over time. This is consistent with the trend towards warmer

daily minimum temperatures observed in @fig-global-plot. Compared to the

location parameter, the other two parameters do not similarly vary over

time. However, it's also completely obvious to expect seasonal variation

in daily minimum temperatures, and a simple harmonic function can be

used to model cyclical variation in seasonal lows. For the

non-stationary case, I fit two candidate models: one modelling annual

and seasonal variation in the location parameter and a second modelling

additional seasonal variation in the scale parameter. In both models,

the location parameter was modeled using:

$$\mu=\mu_0+\mu_1cos(2\pi*doy/365.25)+\mu_2sin(2\pi*doy/365.25)+\mu_3*year$$ {#eq-fit-1}

where $doy$ is the day of the year represented as an integer and $year$

is the calendar year.

```{r fit1-summary, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: tbl-fit1

#| tbl-cap: "Parameter estimates for non-stationary Generalized Extreme Value distribution fit to negative daily minimum temperatures in Fort Collins, CO between 1900 and 2022"

# Non-stationary model 1

fit1 <- fevd(-MnT ~ 1, FCwx,location.fun = ~ cos(2*pi*doy/365.25) + sin(2*pi*doy/365.25) + Year, type = "GEV", span = 123, units = "deg F", time.units = "days", period.basis = "year")

# Non-stationary model 1 summary table

fit1.summary <- summary(fit1, silent=TRUE)

params.ci.fit1 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit1, type = "parameter"),ncol=3))

colnames(params.ci.fit1) <- c("ll","est","ul")

fit1.model.summary <- params.ci.fit1 |>

mutate(estimate = paste(round(params.ci.fit1$est,digits=2)," (",round(params.ci.fit1$ll,digits=2),", ",round(params.ci.fit1$ul,digits=2),")", sep = "")) |>

select(estimate)

fit1.model.summary <- data.frame(params = c("μ0", "μ1", "μ2", "μ3", "Scale, σ","Shape, γ"), fit1.model.summary)

footnote(kbl(fit1.model.summary, format="html", booktabs=TRUE, col.names=c("Parameters", "Estimate (95% CI)"), row.names=FALSE, digits=2, align="lc", escape=FALSE) |>

column_spec(1,width="10em") |>

column_spec(2,width="12em") |>

pack_rows("Location, μ", 1, 4, escape = FALSE) |>

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left"), paste("Negative log-likelihood (NLLH): ",round(fit1$results$value,2),"; Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): ",round(fit1.summary$BIC,2),"; See Equation 3 for the function used to model the location parameter.", sep = ""), footnote_as_chunk = TRUE)

```

Compared to the stationary model, the BIC is about 18% lower for the

non-stationary mode, indicating a much better fit when the annual and

seasonal variation in the location parameter was modeled. In the second

model, the scale parameter was additionally modeled using:

$$\sigma=\sigma_0+\sigma_1cos(2\pi*doy/365.25)+\sigma_2sin(2\pi*doy/365.25)$$ {#eq-fit-2}

```{r fit2-summary, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: tbl-fit2

#| tbl-cap: "Parameter estimates for non-stationary Generalized Extreme Value distribution fit to negative daily minimum temperatures in Fort Collins, CO between 1900 and 2022"

# Non-stationary model 2

fit2 <- fevd(-MnT ~ 1, FCwx,location.fun = ~ cos(2*pi*doy/365.25) + sin(2*pi*doy/365.25) + Year, scale.fun = ~ cos(2*pi*doy/365.25) + sin(2*pi*doy/365.25), use.phi = TRUE, type = "GEV", span = 123, units = "deg F", time.units = "days", period.basis = "year")

# Non-stationary model 2 summary table

fit2.summary <- summary(fit2, silent=TRUE)

params.ci.fit2 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "parameter"),ncol=3))

colnames(params.ci.fit2) <- c("ll","est","ul")

fit2.model.summary <- params.ci.fit2 |>

mutate(estimate = paste(round(params.ci.fit2$est,digits=2)," (",round(params.ci.fit2$ll,digits=2),", ",round(params.ci.fit2$ul,digits=2),")", sep = "")) |>

select(estimate)

fit2.model.summary <- data.frame(params = c("μ0", "μ1", "μ2", "μ3", "σ0", "σ1", "σ2", "Shape, γ"), fit2.model.summary)

footnote(kbl(fit2.model.summary, format="html", booktabs=TRUE, col.names=c("Parameters", "Estimate (95% CI)"), row.names=FALSE, digits=2, align="lc", escape=FALSE) |>

column_spec(1,width="10em") |>

column_spec(2,width="12em") |>

pack_rows("Location, μ", 1, 4, escape = FALSE) |>

pack_rows("Scale, σ", 5, 7, escape = FALSE) |>

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left"), paste("Negative log-likelihood (NLLH): ",round(fit2$results$value,2),"; Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): ",round(fit2.summary$BIC,2),"; See Equation 3 and Equation 4 for the functions used to model the location and scale parameter, respectively.", sep = ""), footnote_as_chunk = TRUE)

```

The fit statistics and model diagnostics generally suggest that the

second model is a better choice between the two non-stationary

candidates. The model could undoubtedly be improved to better fit the

data, but the current version depicts broad patterns in the data

reasonably well and allows for the exploration of model applications.

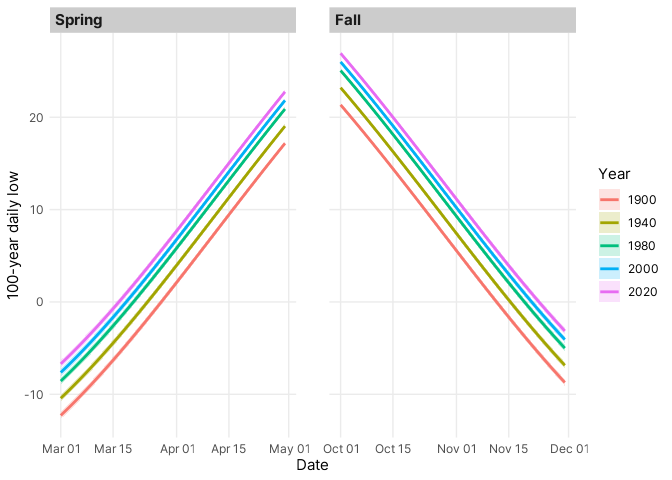

Using the non-stationary model, it is possible to estimate return

periods, return levels, and probabilities associated with extreme low

temperatures. For example, I could estimate the return period (or the

probability) for a -15° F freeze in late December. Instead, I estimated

the 100-year return levels for every day in March, April, October, and

November on five different years contained in the data: 1900, 1940,

1980, 2000, and 2020.

```{r return-levels, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE, fig.showtext=TRUE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: fig-return-levels

#| fig-cap: "Effective 100-year return levels for daily minimum temperatures in Fort Collins, CO on different dates"

v1 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu3 = rep(1900,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1900 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v1),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1900) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v2 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu3 = rep(1940,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1940 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v2),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1940) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v3 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu3 = rep(1980,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1980 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v3),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1980) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v4 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu3 = rep(2000,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsMarApr2000 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v4),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsMarApr2000) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v5 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25), mu3 = rep(2020,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*60:120/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*60:120/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsMarApr2020 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v5),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsMarApr2020) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v6 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu3 = rep(1900,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1900 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v6),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1900) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v7 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu3 = rep(1940,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1940 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v7),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1940) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v8 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu3 = rep(1980,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1980 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v8),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1980) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v9 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu3 = rep(2000,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctNov2000 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v9),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctNov2000) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v10 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25), mu3 = rep(2020,61), phi1 = cos(2*pi*274:334/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*274:334/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctNov2020 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v10),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctNov2020) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

ciRLevels <- rbind(ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1900,ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1940,ci100YrRLevelsMarApr1980,ci100YrRLevelsMarApr2000,ci100YrRLevelsMarApr2020,ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1900,ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1940,ci100YrRLevelsOctNov1980,ci100YrRLevelsOctNov2000,ci100YrRLevelsOctNov2020) |> mutate(Year = rep(factor(c(1900,1940,1980,2000,2020)),each=61,times=2), dt = rbind(data.frame(dt = rep(seq(as.Date("1900/03/01"),as.Date("1900/04/30"),by="days"),5)),data.frame(dt = rep(seq(as.Date("1900/10/01"),as.Date("1900/11/30"),by="days"),5))), Season = rep(factor(c("Spring","Fall")),each=305))

ciRLevels[,1:3] <- ciRLevels[,1:3] * -1

ggplot(data = ciRLevels, aes(x = dt$dt, y = est)) +

geom_line(aes(color = Year), linewidth = 1) + geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=ll,ymax=ul,fill=Year),alpha=0.2) +

xlab("Date") + ylab("100-year daily low") + facet_grid(~factor(Season, levels = c("Spring","Fall")), scales="free") +

theme_nice()

```

The 100-year freezes estimated by the model follow a predictable warming

and cooling trend in the spring and fall (@fig-return-levels), respectively, but the return

levels also warmed considerably, by about 5° F, over each of the

evaluated decades. The confidence intervals are slightly larger during

dates closer to the winter months, reflecting the reduced variability in

daily lows during the warmer summer months.

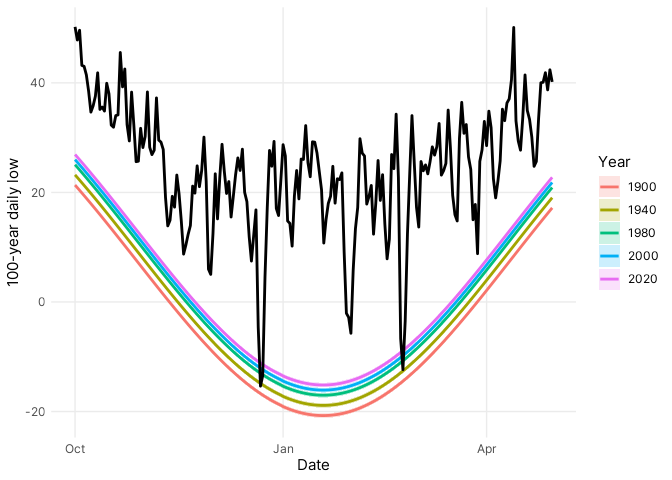

To evaluate the model predictions, I compared the 100-year return levels with daily minimum temperatures for the 2022-2023 winter season (@fig-validation), and the comparison clearly shows it was a cold winter with *two* 100-year freezes on 22 December and 23 February! On most days, however, the daily low temperatures were well above the severe freezes, consistent with expectations for extreme events.

```{r return-levels, echo=TRUE, warning=FALSE, error=FALSE, fig.showtext=TRUE}

#| code-fold: true

#| label: fig-validation

#| fig-cap: "Effective 100-year return levels for daily minimum temperatures (colored lines) in Fort Collins, CO compared to daily minimum temperatures during the 2022-2023 winter season (black line)"

v6 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu3 = rep(1900,212), phi1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1900 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v6),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1900) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v7 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu3 = rep(1940,212), phi1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1940 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v7),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1940) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v8 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu3 = rep(1980,212), phi1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1980 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v8),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1980) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v9 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu3 = rep(2000,212), phi1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctApr2000 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v9),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctApr2000) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

v10 <- make.qcov(fit2, vals = list(mu1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), mu3 = rep(2020,212), phi1 = cos(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25), phi2 = sin(2*pi*c(274:365,1:120)/365.25)))

ci100YrRLevelsOctApr2020 <- data.frame(matrix(ci(fit2, type = "return.level", return.period = 100, qcov = v10),ncol=4))

colnames(ci100YrRLevelsOctApr2020) <- c("ll","est","ul","se")

ciRLevels <- rbind(ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1900,ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1940,ci100YrRLevelsOctApr1980,ci100YrRLevelsOctApr2000,ci100YrRLevelsOctApr2020) |> mutate(Year = rep(factor(c(1900,1940,1980,2000,2020)),each=212,times=1), dt = rbind(data.frame(dt = rep(seq(as.Date("2022/10/01"),as.Date("2023/04/30"),by="days"),5))))

ciRLevels[,1:3] <- ciRLevels[,1:3] * -1

api <- GET("https://coagmet.colostate.edu/data/daily/fcl01.json?from=2022-10-01&to=2023-04-30&fields=tMax,tMin,precip")

FCwx2223 <- do.call(cbind.data.frame,fromJSON(rawToChar(api$content))) |>

mutate(dt = as.Date(time,"%Y-%m-%d"), Dy = yday(dt), Mn = month(dt), Year = year(dt)) |>

select(dt,Dy,Mn,Year,tMin) |> rename(MnT = tMin)

ggplot(data = ciRLevels, aes(x = dt$dt, y = est)) +

geom_line(aes(color = Year), linewidth = 1) + geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=ll,ymax=ul,fill=Year),alpha=0.2) +

geom_line(data=FCwx2223,aes(x=dt, y=MnT), size=1) +

xlab("Date") + ylab("100-year daily low") +

theme_nice()

```